[9 MIN READ]

Remember paper T sheets? Your patient has back pain, so you grab a paper T sheet from the anatomical rack, walk into the exam room, get your history, make some circles and slashes, and your history and physical is all but complete by the time you get back to your desk. Write in (remember writing?) some MDM and ‘ba-da-boom’, the chart is done. The focus was on easy documentation and receiving appropriate reimbursement for the care provided.

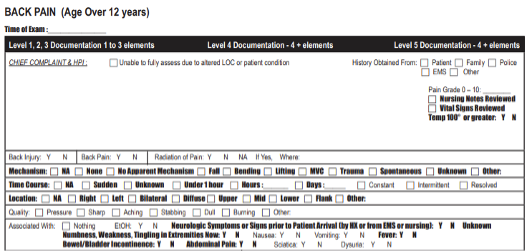

In my group—Midwest Emergency Associates (MEA)—with The Sullivan Group’s (TSG) emphasis on risk and safety, I created a series of paper charts (PromptCharts™) that were chief complaint-based with a heavy emphasis on those elements that relate to getting to an appropriate differential diagnosis and avoiding the failure to diagnose. It’s not rocket science but take a look at the image below.

This is a back pain case. Is the patient running a fever? The answer is in simple bolded font. Is the pain in a single or multiple locations. Any bowel or bladder incontinence?

This is a back pain case. Is the patient running a fever? The answer is in simple bolded font. Is the pain in a single or multiple locations. Any bowel or bladder incontinence?

We fail to diagnose spinal epidural abscess on the first visit in 62% of cases. Why? Because we forget to address many of these key issues. What you see in this image is what is known as a cognitive forcing strategy. Simply put, it’s a reminder to address key issues, and it works.

Fast forward 5 to 10 years to emergency medicine EMRs such as electronic T, Medhost, Wellsoft, Picis, among others. They were still template-based and created by emergency practitioners for emergency practitioners. They were pretty fast and of fairly high quality, and you could build in some cognitive forcing or reminders. Practitioners liked them, and charts were completed in the ED, not at home.

Fast forward again to HITECH and Meaningful Use and the age of Epic, Cerner and Meditech—EHRs that were developed without a focus on clinical practice, speed, efficiency or clinical support. Articles described 4,000 clicks in a single shift. However, veteran practitioners were retiring rather than switching into these “modern” EHRs, and burnout was raging. Practitioners quickly shifted to dictating charts with Dragon Medical One or Fluency Direct using copy/paste, inserting Smartphrases and macros, and ignoring templates and visuals that were cumbersome and time consuming. Even with shortcuts, practitioners often had to finish many of their charts at home. If there was any cognitive forcing, it was through tools such as Best Practice Alerts that turned into white noise and angered practitioners.

Fast forward once again. Within the next five years, your patient interaction will be captured by cell phone or microphone, and physical exams and medical decision-making will be generated by AI. This is the new world of ambient speech. You simply walk into the patient’s room, have an interaction, check the final chart on your tablet, phone or desktop, and sign it.

Picture this—on the journey from a piece of paper with non-intrusive risk and safety reminders in your immediate visual field to making a complete chart via dictation and just “speaking into space,” with the interaction captured and documented through AI. What’s missing?

What’s missing is a cognitive support strategy—reminders in the workflow. What’s happening is documentation has fallen off a cliff. More importantly, there are no prompts in multiple locations to check for fever or pain in patients with back pain. There is nothing to warn against a very abnormal pulse being sent home without re-evaluation. Consider charts created in space without any reference, relying completely on what you think you know.

Did the abdominal pain start in the chest? Movement of pain from above to below the diaphragm is an acute aortic dissection. No one is asking that question anymore. In our recent analysis of over 5,000 chest pain patients over the age of 40, the movement of pain issue was addressed in only 3% of all cases. In over 2,000 ankle injury patients, fewer than 10% of charts addressed a possible Jones or calcaneal fracture, which should be part of every ankle injury examination.

In back pain patients, you perform and document a complete back pain and relevant neuro exam, right? Not in today’s documentation world. Your exam macro doesn’t include a neuro exam; and if it does, it addresses cranial nerves, not cauda equina syndrome. In obvious neuro cases, 25% of the thousands of cases we reviewed had no neuro exam or an inadequate neuro exam.

Today you have autonomous chart creation—either you dictate or AI is making your charts; it’s quick and easy. You have autonomous coding systems, no problem. What is missing is the most critical piece of the entire process. Whether your patient has chest pain, abdominal pain, back pain or an ankle injury, what are the key elements that are often overlooked and lead to a failure to diagnose, morbidity, mortality and malpractice litigation. They used to be on a piece of paper you carried into the room. Now all of that is supposed to be carried in the human memory? That is simply not possible.

Medical error is one of the leading causes of death in the United States. “Failure to diagnose” is the leading medical error in ambulatory specialties such as emergency medicine. We miss spinal epidural abscess in 62% of cases, acute aortic dissection in 28% of cases, and pulmonary embolism in 20% of cases. That is what TSG does—we figure out why. And the answer is the omission of key elements of the history and physical exam that drive an appropriate differential diagnosis.

With that backdrop, bleeding-edge documentation systems provide no mechanism to remind practitioners, no cognitive forcing strategies, and no reminders to drive the thought process toward an appropriate differential diagnosis. Does this sound like a disaster waiting to happen?

On a personal note, I have had two medical interactions in the last 3 months. In the first, a dermatologist used nitrogen to remove facial solar keratoses—a simple 30-second procedure. The next day when I looked at my chart through the portal, I saw that the dermatologist documented a full informed consent discussion. The problem is, that never actually happened. There was no informed consent.

In my second interaction, I went to an urgent care after lacerating a finger in a squirrel trap. The physician sutured it nicely and off I went. I looked at my chart and he had documented “capillary refill intact,” which is absolutely a standard of care evaluation. The problem is, that never happened. He did not check capillary refill. I did because I am an emergency physician, but there are things in my charts that never happened.

For our readers, this is the tip of the iceberg. The appropriate clinical exam is getting lost in the search for speed, efficiency, appropriate billing and coding, and other concerns. It’s time to circle the wagons and address medical errors, documentation, and patient risk and safety in a meaningful way, particularly how to provide practitioners with meaningful reminders and decision support in real time, when it makes all the difference to our patients.

Reference:

Newman-Toker DE, Schaffer AC, Yu-Moe CW, Nassery N, Saber Tehrani AS, Clemens GD, Wang Z, Zhu Y, Fanai M, Siegal D. Serious misdiagnosis-related harms in malpractice claims: The Big Three - vascular events, infections, and cancers. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019 Aug 27;6(3):227-240. doi: 10.1515/dx-2019-0019. Erratum in: Diagnosis (Berl). 2020 May 16;8(1):127-128. PMID: 31535832.