[6 MIN READ]

[6 MIN READ]

(adapted with permission from the original by Dr. Tim Kubacki at https://kubackisinangola.com/)

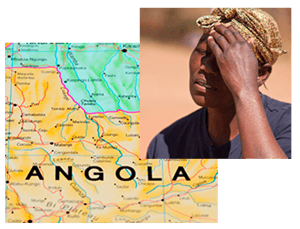

Dr. Tom Syzek: These days we hear so much about the importance of communication and teamwork in avoiding medical errors and how we deliver care at the end of life, I thought for perspective, I would share this case presentation from Dr. Tim Kubacki. Tim is a friend and colleague who left behind the comfortable life of an emergency physician in central Ohio to serve with his family as a medical missionary for 6 years in the jungle interior of Brazil, and for the past 5 years in medically underserved rural Angola. Tim recounts beautifully this medical case of mistaken identity, driving home the point that communication and teamwork are the essence of patient safety, while at the same time describing the only “end-of-life care” available.

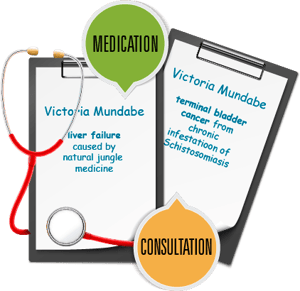

Dr. Kubacki: Two women recently arrived in Cavango within the same week and created a unique situation. With 30+ inpatients, it was several days before we noticed that they had identical first and last names (Victoria Mundabe – changed for privacy), and this caused some confusion. There are no “family” names here, so each member of the family has a unique first and last name. One of the women had liver failure caused by taking all-natural “jungle medicine” and was responding to our treatment well; the other had terminal bladder cancer from chronic infestation of a parasite called schistosomiasis. I had a long talk with the latter and her husband about the nature of her illness and that there was no hope for recovery. These conversations are not uncommon in our rural work where people wait so long to seek help (because of lack of access), and they give this grateful physician an opportunity to present the reality of eternity with love, understanding and wisdom. In a world with the mortality rate still at 100%, it’s a matter we all must soberly address frequently in order to be prepared for the inevitable.

Dr. Kubacki: Two women recently arrived in Cavango within the same week and created a unique situation. With 30+ inpatients, it was several days before we noticed that they had identical first and last names (Victoria Mundabe – changed for privacy), and this caused some confusion. There are no “family” names here, so each member of the family has a unique first and last name. One of the women had liver failure caused by taking all-natural “jungle medicine” and was responding to our treatment well; the other had terminal bladder cancer from chronic infestation of a parasite called schistosomiasis. I had a long talk with the latter and her husband about the nature of her illness and that there was no hope for recovery. These conversations are not uncommon in our rural work where people wait so long to seek help (because of lack of access), and they give this grateful physician an opportunity to present the reality of eternity with love, understanding and wisdom. In a world with the mortality rate still at 100%, it’s a matter we all must soberly address frequently in order to be prepared for the inevitable.

Palliative Care

I emphasized to this beautiful young couple (in their 40s) that each and every one of us will die and that what she was facing was not unique to her, though it always feels so to the person with a terminal illness who is surrounded by healthy people. This life is so brief, whether we die at 15 or 95, and the variables are simply when, how and whether we are prepared. I encouraged Victoria that many people don’t have the opportunity to prepare for their departure from this world, that she had several months to prepare herself, her family and her community for her departure, and that this preparation time was truly a blessing (though painful). I encouraged her to speak often with her heavenly Father and renew her relationship with Him, and I shared with her how much He cared for her, quite apart from any religion. She received my words graciously and courageously before we prayed together for our Father to touch her and give to her all she needed to prepare her to both leave this world and enter the next.

Same Name, Same Look

The other problem with these women’s names being the same is that they were about the same age and bore a striking resemblance to each other, as did their husbands. Several days went by, and I was trying to fly through our inpatients one busy morning when I was handed the chart for one of the women while addressing the other (same name). I didn’t know them well enough to tell them apart, and I recounted to the woman in front of me, whose illness was not terminal, our conversation about her terminal illness! She reacted with shock and confusion; she called her husband and they both asked what had happened that she was now dying! I hadn’t yet realized that we had two women with the same name, as I rarely use the name of the patient when addressing them (apart from using the name on the chart to call her into the exam room), as names are rarely used here in conversation. People call each other “brother,” “sister,” “aunt,” “uncle,” “mother,” “father,” “friend,” etc., and I do the same.

Almost all of my conversations with patients occur through a translator, as few rural people speak Portuguese. I speak Portuguese to the nurse, who translates to the patient’s respective tribal language. We have three common tribal languages in the Cavango region – Nganguela, Mbundo and Choquei. Having three commonly spoken languages has stolen my desire to begin learning them, as they are significantly different from each other and are not variations of the same (as the Latin-based languages are – English, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, etc. – which have similarities, yet are quite different). At this point in the conversation with Victoria and her husband, they are becoming emotional over the fact that her illness is now terminal and I am becoming confused as I note their apprehension. Never thinking that we have two patients with the same name, I concluded that my nurse did not translate my words accurately, and I’m becoming concerned that the gravity of the situation was not communicated accurately.

Almost all of my conversations with patients occur through a translator, as few rural people speak Portuguese. I speak Portuguese to the nurse, who translates to the patient’s respective tribal language. We have three common tribal languages in the Cavango region – Nganguela, Mbundo and Choquei. Having three commonly spoken languages has stolen my desire to begin learning them, as they are significantly different from each other and are not variations of the same (as the Latin-based languages are – English, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, etc. – which have similarities, yet are quite different). At this point in the conversation with Victoria and her husband, they are becoming emotional over the fact that her illness is now terminal and I am becoming confused as I note their apprehension. Never thinking that we have two patients with the same name, I concluded that my nurse did not translate my words accurately, and I’m becoming concerned that the gravity of the situation was not communicated accurately.

Communication

Another cultural norm is that bad news is typically not communicated accurately or directly. As a culture, these people are highly relational, conflict avoiders, and pleasers. When it comes to communicating about a terminal illness, they are typically content with not communicating the truth to the patient (relational peace and temporal contentment is often more important than truth), and instead always offering empathy and hope. On the contrary, I believe in communicating the truth about such an illness gently, but quite directly, so that all involved can better prepare.

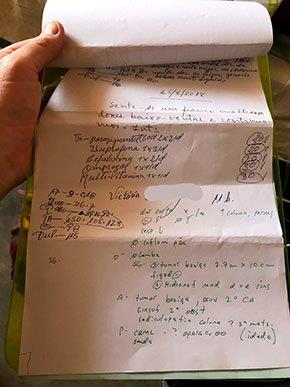

I began to assume that my nurse so compromised my words (with too much emphasis on empathy) that the patient and her husband didn’t understand that she was dying. I called in the nurse who translated the previous discussion and asked how this woman and her husband could not know the reality of their situation after our long and difficult conversation several days back. Our nurse looked confused as well; he asked me for the chart, looked it over, and left the room; he returned after only a few seconds with a second chart and an explanation regarding their (same) names. You can see the chart of one of the two women with the same name here.

We sheepishly explained the situation and apologized to Victoria and her husband and confirmed that she was, in fact, improving. They responded graciously (and thankfully), and suddenly they had much to be grateful for, even though their situation hadn’t changed at all! There’s a pretty powerful lesson there!

Error Analysis: A Low-Tech Solution

We had a team meeting later in the day and explained to everyone on our staff what had happened and that we must be diligent in making sure charts are matched with patients both in consultations and in medication dispensing. This situation was confusing and caused brief concern (trauma) for the patient; but thankfully, neither patient was given the wrong meds, which could have been disastrous. We don’t have electricity, so wristbands, bar codes and scanners are not viable options, but we took some measures to make sure a similar mix-up doesn’t happen again.