[5 MIN READ]

[5 MIN READ]

In a recent blog entitled “The Opioid Crisis: Far From Over,” I reviewed the genesis, magnitude and impact of the opioid crisis in America. Now I will switch gears a bit and look at the trends in the liability of opioid prescribing.

Civil Liabilities

First there’s civil liability, which can and does result in fines and judgment awards. One potential civil liability is overprescribing opioids in quantity and/or frequency over long periods.

This is the classic description of a “pill mill” – essentially a practitioner who sets up shop, has a line out the door, requires little if any explanation or information from patients other than that they have pain, uses pre-printed prescription pads, and has prescriptions flying out the door at the rate of $100 per visit. This is not an exaggeration of what was occurring in southern Ohio and the surrounding states of Kentucky and West Virginia. Another potential civil liability is the failure to maintain accurate records; medical boards and states have laws regarding how to maintain patient records.

There is also the failure to limit opioid prescriptions for known-addicted patients. Consider the 2010 case involving Dr. Conte in Texas, who was found to be negligent in a malpractice death of a man because he prescribed a combination of Vicodin (a narcotic), Soma (a muscle relaxant) and Xanax, all of which are sedating and depress the central nervous system. The judgment was $1.7 million in compensatory damages and $8 million in punitive damages. It was reported that this doctor was associated with 17 clinics; he had pre-printed prescription pads with narcotics on them that could be handed out or sold; and he provided more than 15,000 prescriptions.

There are other potential civil liabilities, such as contributing to a patient’s opioid addiction. In a 2015 case, the West Virginia Supreme Court ruled that patients were allowed to sue doctors and pharmacies for prescribing in the amounts that got them addicted to prescription meds. This is under the legal doctrine of comparative negligence. Yes, the patient was certainly negligent because he/she took the medication; however, negligence can also be alleged on the part of the physician for prescribing outside the norm.

Physicians may also be liable if they fail to check the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) databases per the regulation of their license and the laws of their state. It’s important to note that those practicing near the border of a state must also check the bordering state’s PDMP. This creates an additional burden on providers, but there are potential consequences if one does not comply with these regulations. Civil liability also includes discipline by state medical boards that oversee and discipline physicians and identify outlier prescribing practices.

Criminal Liability

It is rarer that a practitioner would face criminal prosecution for violating the Controlled Substances Act by knowingly and intentionally prescribing outside the usual course of medical practice or for non-legitimate medical purposes. The Controlled Substances Act is a federal law, though a practitioner could also be in violation of a state equivalent. The DEA was busy from 2011 to 2014; adverse DEA actions quadrupled from 88 to 271 cases. These are reported in the National Practitioner Data Bank. A physician may actually face charges of homicide or manslaughter. Though this doesn’t happen every day, there is the notorious case of Dr. Tseng in California. She was convicted of second-degree murder of a patient who died of an overdose of Xanax and Oxycodone, which she prescribed. This was the first opioid murder conviction in the U.S. It was a very high-profile case in California and highly controversial, but Dr. Tseng reportedly had a “pill mill” type of practice, and the jury and prosecutors in the state obviously felt that this amounted to second-degree murder.

Opioid-Related Malpractice Claims

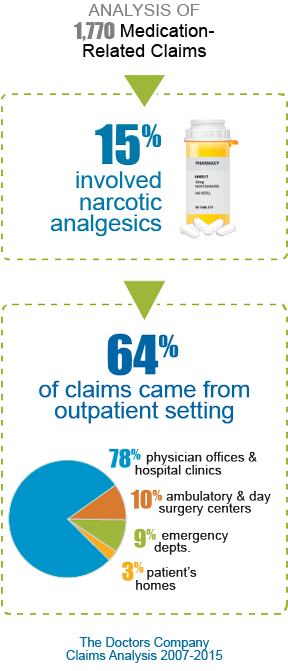

What about opioid-related malpractice claims? A claims analysis by The Doctors Company over an eight-year period showed there were many medication-related claims (1,700); of these, about 15% involved narcotics. Most of these claims came from the outpatient setting (64%): 78% from physician offices and hospital clinics, 10% from ambulatory and day surgery centers, 9% from emergency departments, and 3% from patients’ homes.

What about opioid-related malpractice claims? A claims analysis by The Doctors Company over an eight-year period showed there were many medication-related claims (1,700); of these, about 15% involved narcotics. Most of these claims came from the outpatient setting (64%): 78% from physician offices and hospital clinics, 10% from ambulatory and day surgery centers, 9% from emergency departments, and 3% from patients’ homes.

Most of the allegations in these opioid-related claims were for improper medication management or treatment (70%). Claims related to wrong dose (9%) and wrong medication (3%) may indicate a lack of education or failure to follow evidence-based guidelines; this certainly indicates an opportunity for education. However, these errors represent a minority of claims. There is also an opportunity to intervene and provide education and guidelines to reverse the trends related to improper medication management and treatment.

The data from the claims analysis show the type of medications involved in these opioid claims. Pills are more often implicated in the outpatient setting. For instance, methadone pills were involved in 16% of outpatient claims versus 4% of inpatient claims; the same with oxycodone, another pill. However, injections (e.g., hydromorphone, morphine and fentanyl) are more commonly implicated in inpatient claims. (Hydromorphone, morphine and fentanyl come in other forms as well, but the injectable form is commonly used in the hospital.)

What were the most common medical diagnoses of patients involved in opioid-related claims? For outpatient claims, patients were coming in for pain with a non-specified location (24%), followed by spine-related pain (i.e., back/low back and neck pain at 22%), pain in the joints and extremities (9%), and issues with mental health (6%) and drug abuse/dependence (4%).

The severity of patient injury was much higher in outpatient claims compared to inpatient claims. My guess is that the inpatient mishaps mostly occurred in the hospital while patients were being monitored; thus, there may have been more rapid intervention resulting in less severe outcomes.

The inpatient claims mostly occurred in patients’ hospital rooms after they were transferred from a post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) or ICU in a highly monitored situation. Imagine … a patient is in the PACU/recovery room or ICU where he/she is closely monitored while receiving IV opioids. Then it’s time to be transferred to a general medical-surgical floor where the staffing ratio and monitoring is reduced, and the patient suffers an adverse event related to continued opioid administration. The transition from a closely monitored intensive care-type unit to the floor represents an opportunity for some type of tool to be developed and implemented to cut down on these adverse events.