[12 MIN READ]

[12 MIN READ]

For the past two decades, the U.S. has experienced alarming rates of opioid use, misuse, abuse, and overdose deaths, and we are now ground zero for the opioid epidemic. This epidemic is rife with risks for patients, practitioners, insurers, healthcare organizations, communities, and our entire society. This is the first article in a three-part series in which we’ll explore the opioid epidemic, liability trends related to opioid prescribing, and strategies to reduce harm from opioid prescribing and abuse.

What are opioids?

Opioids are a class of drugs that includes both natural and synthetic drugs. Natural opioids are the ones we know, like oxycodone, codeine, morphine and heroin. They’re called “natural” because they are derived or concentrated from the poppy plant (or parts of the poppy plant). The other classes of opioids are either semi-synthetic or completely synthetic. Completely synthetic opioids are ones such as fentanyl, sufentanil and carfentanil.

Opioids act on nerve cells in the brain and nervous system to relieve pain; that’s their main benefit. As a side effect, they produce pleasurable experiences such as euphoria; this is where the trouble is.

Timeline of the Opioid Crisis

The origin of the opioid crisis really goes back about 40 years when two publications suggested that high-dose opioids could be used to treat chronic pain without any risk of addiction. The first publication was a letter to the editor published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in 1980. This letter stated that less than 1% of patients receiving narcotics while they were hospitalized became addicted; the letter was used to tout the low addiction potential of opioids. This was followed by a study in 1986 suggesting that chronic pain could be managed with opioids without risk of addiction. This was the landmark study, which has since been criticized quite a bit. Soon after this study, drug companies began marketing opioids to physicians for long-term, non-cancer pain. It’s understood that management of cancer pain often requires the use of opioids, but we’re talking about non-cancer pain here. The FDA, Justice Department, and the U.S. Senate investigated these controversial marketing tactics and financial relationships. This resulted in three top drug company executives pleading guilty to criminal charges of misleading clinicians, patients and the FDA about the risks of OxyContin, in particular.

You can see that there was a toxic stew brewing, with low addiction potential being touted and the drug companies marketing opioids. In the midst of all this came a newfound focus on pain as a crisis in itself that demanded attention and relief. This continued in 2001 with The Joint Commission labeling pain as the “fifth vital sign,” giving it equal importance to temperature, pulse, respirations and blood pressure. Ten years later, the Institute of Medicine stated, “Relieving pain should be a national priority.” The pressure shifted to healthcare institutions and providers to pay attention to pain and relieve it. Though it was not explicitly stated that patients should be given opioids, this certainly fed the issue.

Physicians already have the pressure of the toxic stew of policy and profit; then mix in the additional pressure of patient satisfaction surveys. I can tell you from my experience that when you’re measured on patient satisfaction and even your contract as a physician is dependent on patient satisfaction, there is additional pressure to meet patients’ needs, particularly regarding pain. The fallout is that it’s often simpler and less confrontational to write a prescription than to talk to a patient about alternatives to opioids.

Opioids: The Magnitude of the Problem

Consider the current magnitude of the opioid crisis. In 2011, there were more than 420,000 ED visits related to narcotic misuse or abuse. The next year, there were 259 million opioid prescriptions. Mind you, this is not the number of pills, but rather the number of prescriptions written; that’s almost enough for a prescription for every single person in the U.S. By 2013, the number of people in the U.S. who either abused or were dependent on opioids was 1.9 million. Currently, we’re hovering somewhere in the range of 2 million to 2.5 million people who abuse or are dependent on opioids. A recent survey showed that 41% of participants in the Appalachian region ranked drug addiction and abuse as the biggest problem facing their local community. While other healthcare crises are improving (e.g., heart disease and cancer death rates are going down), death rates for opioids are increasing. If this doesn’t define a public health crisis or epidemic, I don’t know what would!

Painkillers in America

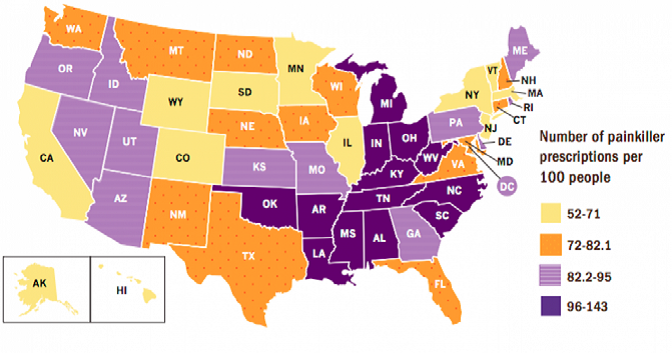

This is a color graphic showing the number of painkiller prescriptions per hundred people back in 2012. The darker colors represent higher rates of prescriptions. You can see that the epicenters are in the South and Midwest, within the Appalachian belt from Mississippi through Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, West Virginia, etc. It has progressed further up into that area over the past few years.

I practiced in Ohio. I see on the news that Montgomery County, which includes Dayton, Ohio, and surrounding areas, is the epicenter for the heroin trade; this is multifactorial and due in part to the crossroads of interstate traffic and socioeconomics of the area. Ohio is always near the top of the list for the number of opioid overdose deaths. Just a few years ago, it was apparent to any ED physician in the area that trouble was arriving in a big way; we started to see more drug-seeking behaviors and more overdose deaths from pills and heroin.

From Acute Pain to Chronic Use

How do we get from a prescription for acute pain to chronic use? One reason is that the duration of a prescription matters. Characteristics of Initial Prescription Episodes and Likelihood of Long-Term Opioid Use – United States, 2006-20151 is an interesting study; it showed that for those patients receiving a one-day opioid supply (e.g., for acute pain such as a broken finger, sprained knee, etc.), 6% will still be using narcotics in one year. For those patients receiving a greater than a one-week opioid supply, almost three times as many (16%) will be drug dependent in a year. The results of this study indicate that it may be possible to limit the spread of opioid use and abuse by changing prescribing habits.

Opioid Overdose Deaths

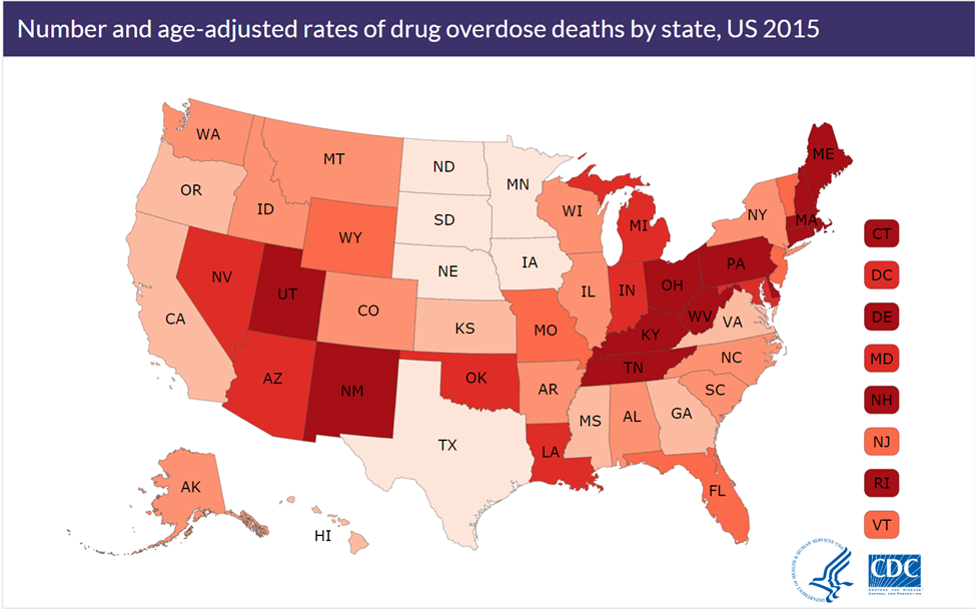

The states with the highest overdose death rates are mostly the same as the states with the highest opioid prescription rates. As mentioned, the Appalachian belt – Kentucky, Ohio, West Virginia, and now up into New Hampshire, which is getting some notoriety as well. Overdose death rates are increasing mostly in the Northeast and the South.

This graphic is similar to the previous one, but this shows the overdose death rates in the U.S. in 2015; the darker the state, the higher the death rate. Pay attention to the South, Midwest and the Appalachian belt.

The Rise of Heroin

Within the past 10 years, healthcare professionals and agencies recognized the epidemic of opioid pill misuse and abuse. Efforts began to address overprescribing by clinicians and the “pill mills” (i.e., a doctor, clinic or pharmacy that is prescribing or dispensing powerful narcotics inappropriately or for non-medical reasons) were shut down. The FBI and DEA cracked down, and tens of thousands of people who started by abusing narcotics pills – either by prescription, diversion, or obtaining pills from others – were cut off from access. The problem was that they were still addicted! This was the genesis of the rise in heroin use that followed. Heroin is simply cheaper and easier to get; it’s $8 to $10 for a dose compared to $80 for one OxyContin pill. Heroin use has increased 37% every year since 2010.

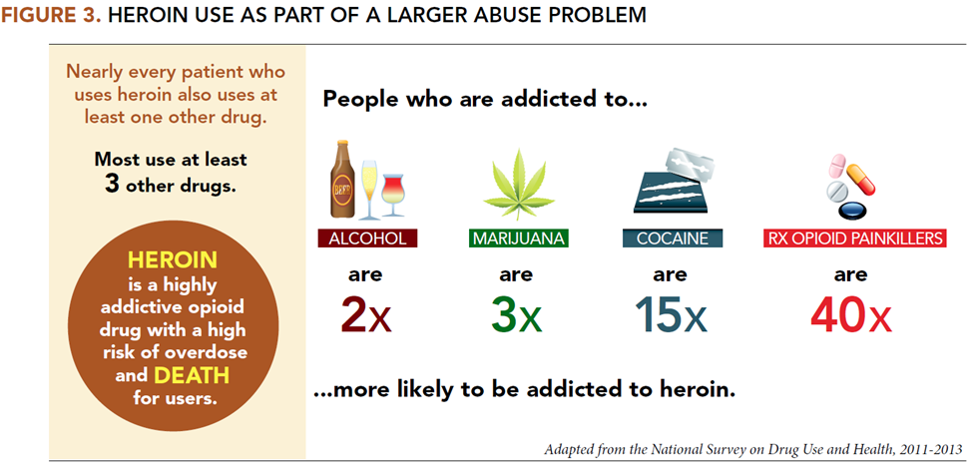

Heroin Addiction is Linked to Other Drugs

As shown by this graphic, heroin use is linked to other drugs of abuse. Nearly every patient who uses heroin also uses at least one other drug; most use three other drugs. It is interesting to see here that people addicted to alcohol, marijuana, cocaine and opioid painkillers are all more likely to be addicted to heroin. Of course, those addicted to opioid painkillers have a much greater likelihood of switching over to heroin, but it’s also true for the other drugs.

NPR ran a story about a surge in opioid overdoses in Cincinnati, Ohio, where I practiced. Over a six-day period, including the weekend, there were 174 overdoses leading to ED visits. This was due to a synthetic opioid, carfentanil, which was used by dealers to cut and mix into the supposed heroin. Why? Because it was cheap. There is no human use for carfentanil; it’s used to tranquilize large animals, including elephants, so it acquired the moniker “elephant tranquilizer.” The problem with carfentanil is that it’s 100 times stronger than fentanyl and 10,000 times stronger than morphine! Imagine … a person would go to shoot up his usual dose from his usual dealer, thinking he was just going to get his usual high, but he actually injected something 100 to 1,000 times stronger than what he was used to. The city just about ran out of Narcan (naloxone); the EMS was overwhelmed. The experience of that weekend corroborated the fact that we were in huge trouble – worse than we ever imaged.

Opioid Impact

On the Economy

The bigger picture is that the opioid epidemic is costing American society an estimated $78.5 billion per year; this is based on a study from 2013. Substance abuse as a whole, including tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs, costs 10 times as much – $740 billion; opioids account for approximately one-tenth of this amount. The figure of $78.5 billion includes not only healthcare costs, but also the cost to the criminal justice system and lost productivity. Where there are illicit drugs, there’s crime. The opioid crisis affects the job economy as well. A recent report indicates that heroin users nod off or fall off at work more often. Even workers whose family members are addicted need more time to deal with opioid-related family emergencies. Opioid users are less productive; they miss twice as many days of work as workers addicted to other drugs. Also, half of unemployed men in their prime age (i.e., their working age) take medication for pain every day. They’re less likely to seek jobs or to be able to pass drug tests, so this has a huge economic effect across the country.

The bigger picture is that the opioid epidemic is costing American society an estimated $78.5 billion per year; this is based on a study from 2013. Substance abuse as a whole, including tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs, costs 10 times as much – $740 billion; opioids account for approximately one-tenth of this amount. The figure of $78.5 billion includes not only healthcare costs, but also the cost to the criminal justice system and lost productivity. Where there are illicit drugs, there’s crime. The opioid crisis affects the job economy as well. A recent report indicates that heroin users nod off or fall off at work more often. Even workers whose family members are addicted need more time to deal with opioid-related family emergencies. Opioid users are less productive; they miss twice as many days of work as workers addicted to other drugs. Also, half of unemployed men in their prime age (i.e., their working age) take medication for pain every day. They’re less likely to seek jobs or to be able to pass drug tests, so this has a huge economic effect across the country.

Adolescents (12 to 17 years)

Tragically, the opioid epidemic affects all ages and walks of life. In 2015, there were 122,000 adolescents (12 to 17 years old) addicted to prescription painkillers; 21,000 of them had used heroin in the past year. Interestingly, most pills were obtained from a friend or relative; pills are just floating around out there being distributed to or stolen from friends or relatives either for fun or profit. The rates of prescription opioids to this group doubled from 1994 to 2007.

Women

Women are particularly impacted by opioids. They’re more likely than men to have chronic pain, get prescription opioids in higher doses, and use the drugs longer than men. The increase in overdose deaths for women from 1999 to 2010 was almost twice as high as for men – up 400% for women compared to 237% for men. Also, heroin overdose deaths tripled in just the last few years.

Characteristics of Communities with High Opioid Prescribing

Communities with higher opioid prescribing and abuse have the following characteristics: they’re small cities or towns, have more residents who are Caucasian, and have more uninsured and unemployed people. This is the central focus of the best-selling book, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, in which the author recounts the Appalachian values of his rural, impoverished upbringing and their relation to the social problems of his hometown in Ohio.

The following statistic is a big one:

The amount of opioids prescribed in 2015 was enough to medicate every person in America around the clock (24/7) for three weeks.

Talk about epidemic! I’d say we need to really consider changes in the way we approach opioid prescribing.

Who Prescribed the Medications to Overdose Victims?

One study of overdose deaths in San Diego revealed some very interesting findings and red flags. In this 12-month study, researchers looked at 254 drug overdoses in San Diego; it was not limited to opioids. They labeled this “Death Diaries,” not because patients kept diaries, but because the records reviewed from the state Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) were like diaries; they told the story of why there were overdoses and what happened. The PDMP records showed that for many of those who overdosed, there were problems; they were prescribed drugs by multiple clinicians, there were potentially dangerous drug interactions on record that were ignored, there were escalating dosages, and there was evidence of doctor shopping. Clearly, at the time, the PDMP wasn’t used effectively to help deter the problem; however, the PDMP gained notoriety as a way to identify patterns in drug overdose deaths.

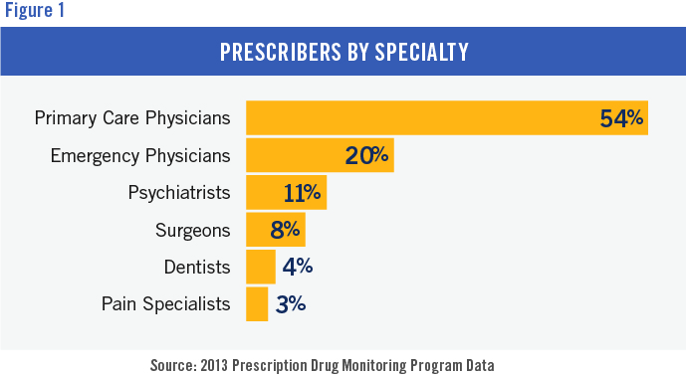

The study showed that over half of the prescribers to overdose victims were primary care physicians, followed by emergency physicians, psychiatrists, surgeons, and even dentists. Interestingly, but not surprising to me, pain specialists were on the bottom of the list. Why? Because they have contracts with their patients, they perform drug testing, etc. The pain management specialty itself probably does the best job of monitoring and controlling prescriptions.

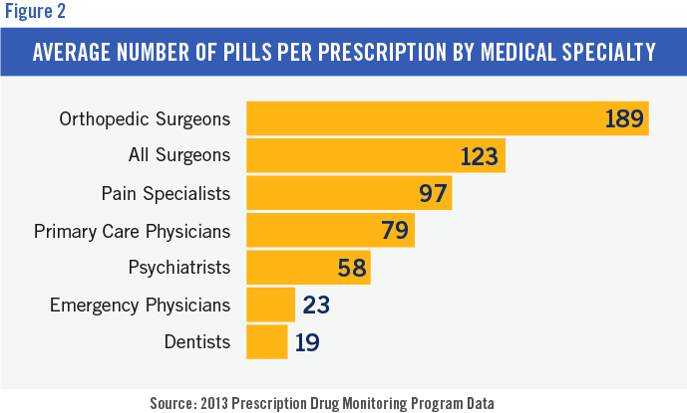

The study also showed the average number of pills per prescription by medical specialty. Surgeons led the pack; orthopedic surgeons were first, followed by all surgeons. Several studies indicate that opioid pain medication is overprescribed after a surgical procedure. Surgery is painful, and practitioners want patients to have enough medication to relieve pain; but there is a growing awareness of limits and alternatives to opioids in surgical patients. Several surgical societies have addressed and adopted evidence-based/best practices.

Summary

The data regarding opioid misuse, abuse and overdose is very alarming and really quite depressing. When I was in the middle of an ED in the Cincinnati area, EMS would bring somebody in unconscious, barely breathing. I’d find out he was an employed college graduate from a middle-class family, but he had been abusing prescription opioids. He then switched to heroin and overdosed to the point where we could not resuscitate him. We essentially had a heroin overdose in every ED every day, and in some places many times a day. As a result, EMS has more experience and knowledge about opioid overdoses and Narcan (naloxone) than many physicians.

Awareness is now peaking; the statistics I talked about today are readily available, and there are many headlines as the media/press has increasingly taken this up. While awareness and recognition is finally getting to where it should be, the solution is not. There are very few things as powerful as an opioid addiction; there’s no immediate answer to solve all the issues of the opioid crisis. Unfortunately, it appears that the number of addicted individuals and overdose deaths has not yet reached its peak. I hope I will be proven wrong, as the problem receives more attention and action by healthcare professionals, communities and legislators.