Over the next eight weeks, we will be providing information on EHRs/EMRs that have proven to improve patient safety, reduce medical errors and reduce litigation. In this first week, we provide historical context on the events leading up to today’s current state of electronic provider documentation. This series aims to help shed light on the improvements available for EMR physician documentation and to provide key takeaways to implement into your providers’ workflow.

Over the next eight weeks, we will be providing information on EHRs/EMRs that have proven to improve patient safety, reduce medical errors and reduce litigation. In this first week, we provide historical context on the events leading up to today’s current state of electronic provider documentation. This series aims to help shed light on the improvements available for EMR physician documentation and to provide key takeaways to implement into your providers’ workflow.

History

A very brief chronology of physician documentation shows medical practitioners handwriting medical records through the mid-1990s, then converting to “dictation-transcription” systems or medical voice-activated dictation, and then on to complaint-oriented one- or two-page paper templates for the next decade.

By the turn of the century, medical entrepreneurs had developed chief complaint-based electronic medical records. These were boutique systems, developed for medical specialty niches that were typically created by physicians for physicians. They were generally intuitive and fast and followed the medical specialties workflow. They were labelled “boutique” because they were focused on a specific specialty and had to be incorporated into the hospital’s underlying enterprise health record; they were not part of the hospital’s enterprise system.

Physician satisfaction with the EMRs was relatively high, as a patient’s record could often be completed contemporaneously during the visit and the EMR design supported clinical decision-making. In the boutique era, practitioners did not stay for hours after a workday to complete charts, nor did they go home to log back into the system and “do their charts.”

Hospitals initially relied upon medical leadership to identify best-of-breed EMRs, which they implemented in key specialty areas such as emergency departments and anesthesia. Over time, the number of such programs grew to avalanche proportions, and IT teams were simply overwhelmed by the logistics of coordinating many if not hundreds of boutique systems to the hospital’s underlying enterprise system. Looking at the big picture, this trajectory was not tenable. Imagine not only the initial install with potentially hundreds of API connections, but then dealing with new version releases of both the boutique programs and the enterprise system and keeping the connections up to date. Multiply this by hundreds of such programs over time, and this became an incredible burden on the nation’s hospitals.

Hospitals initially relied upon medical leadership to identify best-of-breed EMRs, which they implemented in key specialty areas such as emergency departments and anesthesia. Over time, the number of such programs grew to avalanche proportions, and IT teams were simply overwhelmed by the logistics of coordinating many if not hundreds of boutique systems to the hospital’s underlying enterprise system. Looking at the big picture, this trajectory was not tenable. Imagine not only the initial install with potentially hundreds of API connections, but then dealing with new version releases of both the boutique programs and the enterprise system and keeping the connections up to date. Multiply this by hundreds of such programs over time, and this became an incredible burden on the nation’s hospitals.

A fundamental change occurred with the enactment of the HITECH Act and the associated Meaningful Use regulations in the mid-2000s. The law and regulations were designed to expedite the implementation of EHRs across the nation in order to improve quality and sharing of health data. The Meaningful Use (MU) criteria were quality-related; improved availability of health records across the enterprise was conceptually a step in the right direction. If the hospital or hospital organizations met MU criteria, they received a significant level of government funding to support their EHR development; so significant, in fact, that many hospital organizations immediately set upon the path to ensuring that they met MU criteria to obtain funding.

If the goal of HITECH and MU was to expedite the incorporation of EHR into the medical marketplace, it was a huge success. In determining how to quickly and efficiently meet MU criteria and receive funding, hospitals found that there were just a handful of large EHR vendors prepared to address the entire enterprise and meet MU criteria, such as Cerner, EPIC and MEDITECH. However, in the mid-2000s, whether by design or not, the popular EHRs were not compatible with the boutique systems developed in the prior decade.

Between 2005 and 2015, there was a huge market pendulum swing from the boutique programs to the clinical programs inside of the newly purchased EHR programs. For example, in the early 2000s, one large health system purchased a boutique EMR for its 100+ emergency departments. It was well liked by emergency physicians, it was fast, and it provided reasonable clinical decision support. The organization used MEDITECH as the underlying EHR and had “connected” the boutique program to MEDITECH. However, when the organization recognized that the boutique within MEDITECH could not meet emergency department MU, the organization deinstalled the system and began using the MEDITECH emergency medicine program known as PDO. A similar scenario played out in many organizations around the country following HITECH.

Here is a core issue. Using the market leaders as examples once again, EPIC, Cerner and MEDITECH were all originally designed to meet a particular need. EPIC’s life began as a primary care program; Cerner was developed as a pathology program; and MEDITECH was considered a great database program with good billing and coding functions. All were developed further to support the needs of the hospital enterprise, but none were built with any focus in the diverse clinical specialties. Although all have modules for emergency medicine, anesthesia, hospital medicine and others, none come close to the quality, speed, workflow and clinical support of the boutique applications. Although they helped hospitals meet MU and thus capture government funding, medical practitioners were forced to adopt new and dramatically inferior documentation systems.

The days are gone when practitioners have any say in which EMR will best serve their patients’ and communities’ needs. Organizations have chosen the large EHR systems that promised Guidance through the MU process.

That is not to dismiss the value of the popular EHR systems. They help organizations meet critically important medical data functions. For example, data from a primary care office visit will be immediately available in the emergency department should the patient require a subsequent visit; a patient’s past history, labs and imaging are available to all practitioners. But these organizations have completely missed the boat on perhaps the key bottom line to any such system — helping the practitioner provide the highest quality patient care possible and meeting the specific workflow of each specialty. That has simply not been a priority or a focus of any of the large EHR systems or they simply have not had the time to get around to it.

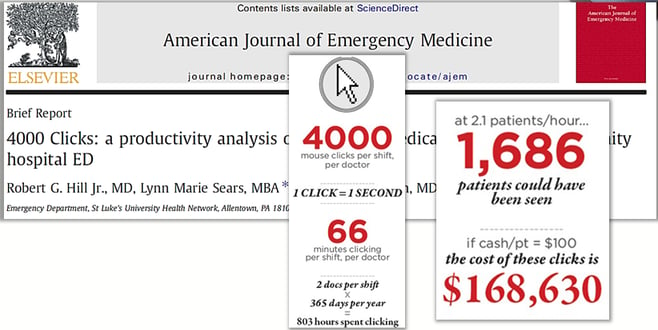

This fact is supported by a number of studies and publications that focus on issues across several specialties related to the physician documentation experience while using the clinical applications inside the commonly used EHR systems. The following graphic is from an emergency medicine publication reporting on the number of mouse clicks it takes to create medical records in a typical shift in an emergency department.

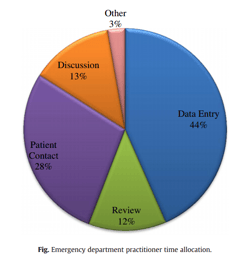

In yet another publication, the authors point out that far too much time is spent at the computer documenting the patient encounter, and too little at the patient’s bedside.

In yet another publication, the authors point out that far too much time is spent at the computer documenting the patient encounter, and too little at the patient’s bedside.

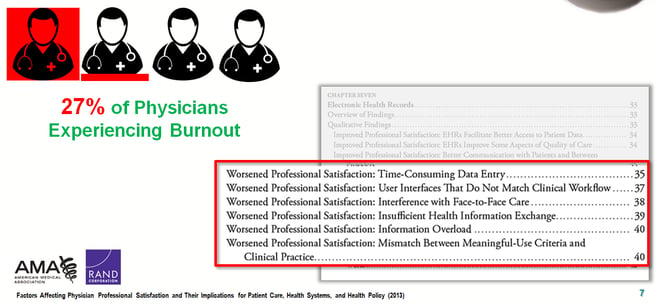

The American Medical Association recently joined forces with the Rand Corporation to identify the cause of increasing rates of physician burnout. An entire chapter was devoted to the EHR; it contained some positive aspects, but also many significant negatives in the EHR experience.

The EHRs now dominating the marketplace contain physician documentation programs that were not built by or for physicians. They were not developed to support workflow, efficiency or clinical decision support. The inefficiencies keep practitioners away from the patient’s bedside, cause slow throughput, impair workflow and create dissatisfaction; more importantly, they may actually create risk as practitioners focus on documentation tasks instead of patient interaction.

This is a burning platform that should drive change. The huge investments made in the nation’s EHRs means they are likely here to stay; but they are foundations upon which good clinical EMRs can be built. Thus, it is imperative that we work with those programs to provide practitioners with the EMR tools required to provide the highest quality care and to implement programs that mirror the practitioner’s workflow, seamlessly provide clinical decision support, assist the practitioner in delivering evidence-based medicine, and keep our patients safe.

Opportunities

Where there are problems, there are also opportunities. EHR organizations need a renewed focus on the medical specialties with a focus on developing or incorporating EMR programs that support, facilitate and improve the physician and patient experience. Some general areas of focus include the following:

- Specialty-specific clinical content

- User interface design that reflects the specialty patient experience

- Conditional risk, safety and quality Guidance

- Clinical decision support inside the user interface

- Human factors engineering

- Evidence-based medicine and best evidence inside the EMR workflow

- Fast, efficient charting

- Alignment of clinical practice patterns

In the next several weeks, we will dive into each specific area to explore the benefits on workflow and patient safety.