Providing care to psychiatric patients in the emergency department is a challenge for many reasons.

Providing care to psychiatric patients in the emergency department is a challenge for many reasons.

- Emergency physicians often receive insufficient training in behavioral emergencies.

- ED personnel are uncomfortable evaluating and treating these patients.

- ED staff may harbor negative attitudes toward behavioral health patients.

- Resources such as consultants and inpatient beds are lacking.

- The hectic ED environment can lead to iatrogenic escalation of psychiatric crises.

For the ED, however, the greatest risk and safety issue related to behavioral health is the appropriate evaluation and protection of the suicidal patient in the ED. We present 2 case studies to illuminate the uncommon but preventable catastrophe of suicide in the ED.

Download audio and listen to this case.

Case #1

A 43-year-old man with a history of depression presented to the ED with the complaint of feeling suicidal. The patient had cut himself after an argument with his wife. His family called 911; the police and EMS responded and transported him to the ED. The initial suicide screening revealed that the patient did not want to live and intended to kill himself. Because of this initial screening, the ED nurse initiated “high risk behavioral health precautions.” The physician ordered labs, suicide precautions with one-on-one observation, and evaluation by the on-call mental health counselor. Everyone agreed that the patient was at high risk of suicide and would require inpatient psychiatric admission.

The medical record showed that the patient was “placed in a gown and a safe ED room” and that suicide precautions were initiated. The ED nurse charting — performed at 15-minute intervals — indicated that security was at the patient’s bedside. While awaiting psychiatric admission and after several hours of observation, security briefly left the patient’s room; they returned to find the patient unresponsive, cyanotic, and hanging from the cardiac monitor with the monitor wires wrapped around his neck. The patient did not survive despite a code blue resuscitation.

Overview of Suicide in Hospitals

Before we address the specifics of this case, let’s talk in general about suicide in the hospital setting. Although hospital suicide is an uncommon occurrence, it is considered a preventable sentinel event by The Joint Commission (TJC). Hospital suicides have occurred in various locations, including psychiatric hospitals, psychiatric units in general hospitals, medical-surgical units, and emergency departments.

Before we address the specifics of this case, let’s talk in general about suicide in the hospital setting. Although hospital suicide is an uncommon occurrence, it is considered a preventable sentinel event by The Joint Commission (TJC). Hospital suicides have occurred in various locations, including psychiatric hospitals, psychiatric units in general hospitals, medical-surgical units, and emergency departments.

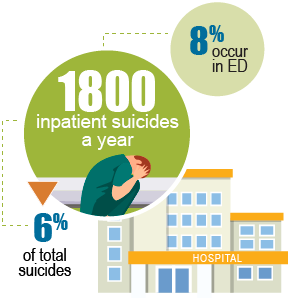

During the 5-year period from 2012 to 2016, an average of 85 hospital suicides per year were reported to TJC. This statistic underestimates the true incidence of hospital suicide because according to TJC: “The reporting of most sentinel events to The Joint Commission is voluntary and represents only a small proportion of actual events.” Data from other sources reported in 2012 that there were 1,800 inpatient suicides yearly, representing 6% of the total suicides in the United States. One report estimated that 8% of all inpatient suicides occur in the ED, representing a small but significant fraction of inpatient (hospital) suicides. Methods of suicide have included strangulation, intentional drug overdose, hanging, jumping from a height, and cutting with a sharp object.

Case #1 Discussion

The patient in this case clearly had risk factors for suicide (depression, previous attempt, social stressors) and was correctly identified as a high risk for suicide by the nurse, ED physician, and mental health counselor. There was no difficulty in establishing the diagnosis of suicidal depression in crisis. The staff took appropriate action, including placing the patient in a gown, initiating “high-risk behavioral health precautions,” consulting with the mental health counselor, and physician orders consisting of suicide precautions with one-on-one observation in a “safe ED room.”

So what went wrong? Two things for sure. First, the patient was left alone when the security guard exited the room, no matter how briefly. In another case of ED suicide, the patient requested privacy while she took a sponge bath in bed. This patient hung herself with bedclothes while the privacy curtain was drawn. Suicidal patients require continuous observation. Even a few minutes lapse in visual monitoring can allow a determined patient enough time to attempt suicide, as proven in these tragic cases.

Secondly, the ED room that was documented to be “safe” in the patient’s medical record instead turned out to contain a lethal means of suicide — the cardiac monitor wires.

These errors violated the guidelines published by TJC in a Sentinel Event Alert in February 2016 that addressed the issue of “Detecting and Treating Suicide Ideation in all Settings.” This Alert acknowledged the unabated problem of hospital suicide and included the following recommendations:

These errors violated the guidelines published by TJC in a Sentinel Event Alert in February 2016 that addressed the issue of “Detecting and Treating Suicide Ideation in all Settings.” This Alert acknowledged the unabated problem of hospital suicide and included the following recommendations:

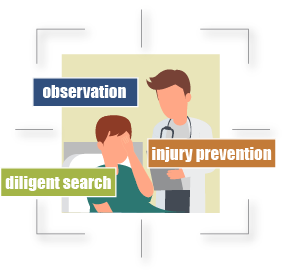

- Keep patients in acute suicidal crisis in a safe healthcare environment under one-to-one observation.

- Do not leave these patients by themselves.

- Check these patients and their visitors for items that could be used to make a suicide attempt or harm others.

- Keep these patients away from anchor points for hanging and material that can be used for self-injury.

The Alert also pointed out that some specific “lethal means that are easily available in general hospitals and that have been used in suicides include: bell cords, bandages, sheets, restraint belts, plastic bacs, elastic tubing and oxygen tubing.” This list is not exhaustive; we can add cardiac monitor wires and just about any object left in a patient’s room. Most of us have surely witnessed suicide methods involving other lethal means.

The 7-page Sentinel Event Alert from TJC also provides guidance regarding the detection of suicidal ideation in non-acute or acute care settings, taking immediate action and safety planning for suicidal patients, behavioral health treatment and discharge, and education and documentation.

Case #2

Before a thorough evaluation could take place, a suicidal patient in the ED started screaming at the nurses that she wanted to leave. The patient was restrained supine by all four limbs. The 2 beds in the ED designated for behavioral health patients were full, so they put the patient in a procedure room, away from the nurse’s station. Since the patient was screaming and yelling, the ED staff was happy to isolate the patient in a room. The staff allowed her to keep her clothes on so as not to agitate her any further. They did not find weapons on her, but they also did not perform a diligent search for other objects that could be used to inflict harm.

Before a thorough evaluation could take place, a suicidal patient in the ED started screaming at the nurses that she wanted to leave. The patient was restrained supine by all four limbs. The 2 beds in the ED designated for behavioral health patients were full, so they put the patient in a procedure room, away from the nurse’s station. Since the patient was screaming and yelling, the ED staff was happy to isolate the patient in a room. The staff allowed her to keep her clothes on so as not to agitate her any further. They did not find weapons on her, but they also did not perform a diligent search for other objects that could be used to inflict harm.

Patient Safety: Searches & Environmental Dangers

Before divulging the outcome of case, we should emphasize that hospitals must be diligent to identify environmental factors that contribute to the patient's ability to commit suicide. Staff in the ED and other hospital locations are responsible for the safety of all patients in their units. Therefore, once a patient comes in and is determined to be suicidal, the hospital, physicians and staff are all responsible for ensuring that patient’s safety at all times.

When there is a suicidal patient in the ED, it is essential to search for and remove materials that can be weaponized and used for harm such as nurse call buttons, bandages, plastic bags, elastic tubing, oxygen tubing, cleaning supplies and chemicals, etc. Some experts contend that metal detectors should be used to screen every person entering the ED, including patients, families and visitors.

The Burning Bed

Returning to our agitated and restrained patient in the back-hall procedure room, she continued to scream behind the closed door. Despite restraints, the patient was able to reach and remove a lighter from the pocket of her overalls and used it to ignite the curtains. True story! The burning curtains fell on her, catching her and the gurney on fire. When the staff noted smoke billowing beneath the door, she was rescued, but not before she suffered smoke inhalation and major burns over 43% of her body.

Case #2 Discussion

![]() What went wrong? No fewer than 4 things.

What went wrong? No fewer than 4 things.

- Failure to adequately search the patient

- Failure to place the patient in a secure, safe space for care

- Failure to comply with one-to-one observation

- Failure to properly assess a suicidal patient

For starters, searching the patient for weapons alone was not adequate. The search should have been more thorough to detect and remove any potentially harmful objects. Secondly, the procedure room in the back hall had curtains and other objects remaining in the room, which meant it was not a safe place to care for an agitated, suicidal patient. Although there is some debate in the psychiatric literature about whether clothing should be removed and the patient dressed in a gown, a conservative recommendation is to remove their clothing and have them dress in a hospital gown — not just a regular gown, but one of special design or color. The color of gown and/or wristband can be used to identify the patient as high risk for suicide, serving as visible notice to everyone that the patient is under suicide precautions and cannot be allowed to leave.

What else went wrong? The ED staff did not use one-to-one observation for a suicidal patient and they did not properly assess her. All they really knew was that the patient was screaming and disruptive. Annoyed by this ruckus, they decided to restrain her and place her somewhere out of sight and hearing.

In a November 2017 special report on Suicide Prevention in Health Care Settings, TJC provided additional guidance regarding the prevention of suicide. Here are 2 relevant recommendations specific to the ED:

- There are two main strategies to keep patients with serious suicide ideation safe in emergency departments: 1) Place the patient in a “safe room” that is ligature-resistant or that can be made ligature-resistant by having a system that allows fixed equipment that could serve as a ligature point to be excluded from the patient care area (for example, a locking cabinet); and 2) keep the suicidal patient in the main area of the emergency department, initiate continuous 1:1 monitoring, and remove all objects that pose a risk for self-harm that can be easily removed without adversely affecting the ability to deliver medical care. Organizations should have policies, procedures, training, and monitoring systems in place to ensure these are done reliably.

The Joint Commission does not mandate the use of “safe rooms” within the emergency department. Organizations should do all of the following to protect patients:

The Joint Commission does not mandate the use of “safe rooms” within the emergency department. Organizations should do all of the following to protect patients:

- Screen all patients presenting with psychiatric disorders for suicidal ideation (NPSG 15.01.01).

- Formally assess the risk of a suicide attempt among patients with suicidal ideation (“secondary screening”).

- Conduct a risk assessment for objects that pose a risk for self-harm and identify those objects that should be routinely removed from the immediate vicinity of patients with suicidal ideation who are cared for in the main area of the emergency department.

- Have a protocol for removing all movable items that could be used for self-harm from within reach of a patient with suicidal ideation.

- Have protocols for monitoring patients with suicidal ideation, including the use of the bathroom and how to ensure that visitors do not bring objects that the patient could use for self-harm.

- Have a protocol for qualified staff to accompany a patient with serious suicidal ideation from one area of the hospital to another.

- Train staff and test them for competency on how they would address a situation with a patient with serious suicidal ideation.

- Patients with serious suicidal ideation must be placed under demonstrably reliable monitoring (1:1 continuous monitoring, observations allowing for 360-degree viewing, continuously monitored video). The monitoring must be linked to the provision of immediate intervention by a qualified staff member when called for. The organization has a defined policy that includes this detail.

The cases presented illustrate some of the risks and errors that occur in the care of suicidal patients in the emergency department. Even when most of the safety guidelines are followed, a seemingly brief and minor lapse in protocol can result in attempted or completed suicide. Once an individual in the ED or hospital has been identified as suicidal, the responsibility for ensuring the patient’s safety falls entirely upon the staff, nurses and physicians involved.